Marshall Lee GoreThis is a man who was a childhood friend of my brother, they went to school together, and when they were older they had gotten in trouble together. My Brother had come to live with me after he divorced his wife, he was trying to straighten his life out, and he had been good for a long time. On March 13th, after Marshall had been out of my brother's life for at least a year, Marshall came to my house to see him. My brother wasn't home the first time he came, and he asked if he could wait for him. I told him no, he seemed like he was on crack or something, just very twitchy and cagey.

I told myself it was just me not trusting him at all ever, and wanting to keep my little brother out of trouble if possible. My memory is not 100% on this but when he came the first time, he was driving a black car. According the the court records he was not driving when he came to my house the second time, and took a cab when he left.

My brother let him in and they sat in his room talking for a while. It was time for me to go to bed and I just kept thinking I didn't feel comfortable with him in the house, but I figured my little brother was a big boy. I locked my little family, my 3 year old son and my husband and myself, into our part of the house. At most I thought I was probably dealing with a crack addiction and risking losing TV's and anything else he could sell for a fix.

Until I tried to close my eyes, I could not sleep at all, every time I tried to close my eyes I would get a visual flash of my brother being held in a choke hold or with a knife to his neck. Eventually I got up and told my brother his friend had to go, he was not spending the night I couldn't sleep, and I needed to sleep (and I was getting paranoid). So he left.

So for some months previous to deciding to visit my brother, he had been doing this:

January 30, 1988, 19-year-old Susan Marie Roark, a Tennessee college student, disappeared. She was last seen alive with Gore leaving a trailer park in Bradley County, Tennessee.

The following day, Gore murdered her, inflicting trauma to her neck and chest. He then stole her car, a 1986 black Ford Mustang, and dumped her body off a forest road in Columbia County, Florida.

On February 14, he attacked a Miami waitress, Robyn Novick, raping and stabbing her. The waitress survived the attack, and Gore abandoned the stolen Mustang in Miami, where it was found the same day

Robyn Novick was killed between 9 p.m. and 1 a.m. on March 11 into March 12, 1988. Novick was last seen alive on March 11, 1988,

Gore murdered Robyn Novick by stabbing her in the chest and tying a belt around her neck. He stole her car and dumped her body in a trash heap near Homestead(south of Miami). According to a medical examiner, the cause of death was mechanical asphyxia and stab wounds.

early morning of March 12, Gore was seen driving Novick's automobile. (yellow Corvette)

a friend of Gore's, (Restrepo) testified that Gore arrived at his home driving a yellow Corvette with a license plate reading "Robyn."

Gore also asked Restrepo to accompany him to Coconut Grove. On the way to Coconut Grove, Gore lost control of the vehicle and "wrecked" the Corvette. Gore attempted to drive the vehicle away from the scene of the accident, but abandoned the vehicle a few blocks away.

The following night, March 13, Gore went to the house of a friend, Frank McKee, and asked him if he could borrow some money and stay the night. Gore stated that the police were looking for him. Gore also informed his friend that he had recently been in a car accident involving a yellow Corvette and that he had lost some jewelry. McKee refused to allow Gore to spend the night and Gore subsequently left in a cab.

on March 14, Gore attacked a third woman.

He abducted 32-year-old Tina Coralis, a nude dancer from Broward.

He left her for dead by the side of a road near to where he had dumped Novick's body. Gore then stole her car and drove off, abducting her 2-year-old son Jimmy, who was still sitting in the back of the vehicle

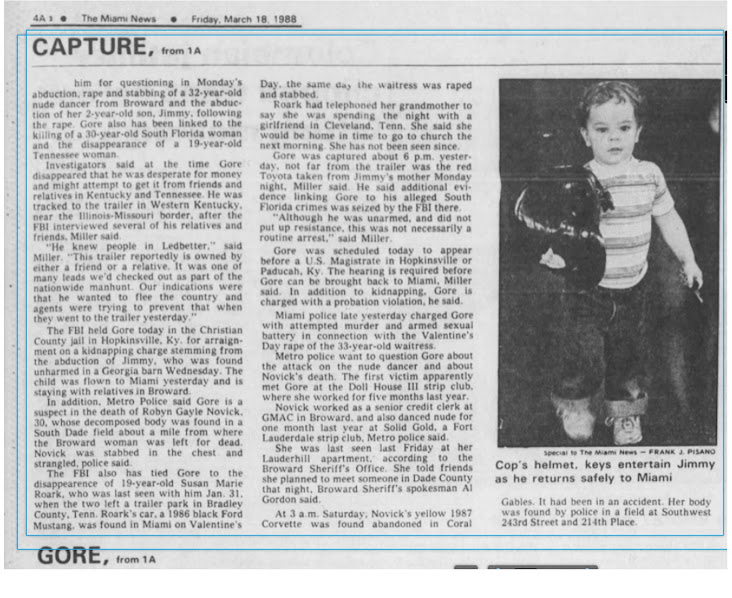

Coralis survived the attack and alerted the police. After attacking Coralis, Gore fled the state and headed to Georgia, where he left Jimmy, locking him in the pantry of an abandoned barn before heading north towards Kentucky.

On March 16, while police were searching for Jimmy, they came across the body of Novick, who was found near to where Gore had left Coralis. On March 16, Jimmy was found unharmed.

Gore was tracked to a trailer in Paducah, Kentucky.

He was captured on March 17, unarmed and without incident. Near to the trailer, police found the stolen car that belonged to Coralis.

So it was less than a week after we last saw him, that I saw his face on my TV, early in the morning while eating cereal with my little boy!

In April 1988, Columbia County deputies found Roark's body.

On October 1, 2013, Gore was executed via lethal injection at Florida State Prison.[14] His last meal was just a can of Coca-Cola, as he rejected his original requested last meal of sausage and pepperoni pizza.

He had no final words

-----------------

Below are the sources for information that helped me finally after all of these years to figure out the time line. I'm happy the info waited for me to be ready. This was way more, "too close for comfort" than I ever knew.

My brother died of Cancer on June 15th 2013, a few Months before Marshall Lee Gore was executed...Life is weird...

Protesters outside the execution of Marshall Lee Gore

Since my teen years I had been totally against the death penalty, and I still don't think it is the most just solution for some. But when they took "Marty" away in a bag it felt final, and okay, to me. I imagine maybe even more so for the families of the women.

When my Mother found out what Marshall had done, her comment was, basically: But he was so nice, and polite, I would never imagine in a million years. My mother had known him since he was a teenager, he spent time at her house with my brothers.

I had met him maybe twice when he was young, and he made me uncomfortable then, because it felt like he was hitting on me and I was in my 20's and he was maybe 15 at most. He was practicing his smooth moves and pick up lines. My older sister said the same thing about him. I hope we never looked at each other and said he's gonna be a lady killer one day, he was a pretty cute kid.

Beyond this point is just basically a pin board

Marshall Lee Gore

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Marshall Gore

Born Marshall Lee Gore

August 17, 1963

Chicago, Illinois, U.S.

Died October 1, 2013 (aged 50)

Florida State Prison, Raiford, Florida, U.S.

Cause of death Execution by lethal injection

Conviction(s) First degree murder (2 counts)

Criminal penalty Death

Details

Victims 2+

Span of crimes January 31–March 15, 1988

Country United States

State(s) Florida

Date apprehended March 17, 1988

Marshall Lee Gore (August 17, 1963 – October 1, 2013)[1] was an American convicted murderer and rapist who was executed by the state of Florida for the 1988 murders of two women.[2] He also raped and attempted to murder a third woman before kidnapping her 2-year-old son. Gore was convicted, sentenced to death, and subsequently executed in 2013 at Florida State Prison by lethal injection.[3]

Early life

Gore was born on August 17, 1963, in Chicago, Illinois, and grew up in a troubled family. He was the second of five children born to Jimmy Joe Gore and Brenda McCurry Gore. His parents married in Chicago in 1961, where Gore grew up. They later moved to the Miami area. The Gore family frequently got into trouble with the law. Jimmy Joe Gore was arrested on felony charges in three states. Some of Gore's siblings were also arrested for various offenses. Gore was arrested at least eight times for multiple offenses throughout the 1980s in Miami-Dade County, Florida. His parents' marriage fell apart in 1985 due to abuse and violence, with the couple officially getting a divorce in 1987. Gore stayed with his father in Florida and worked as a bouncer at a bar his father owned.[4]

Murders

On January 30, 1988, 19-year-old Susan Marie Roark, a Tennessee college student, disappeared. She was last seen alive with Gore leaving a trailer park in Bradley County, Tennessee. Roark phoned her grandmother and told her she was spending the night with a girlfriend in Cleveland. She said she would be home the following morning in time for church. The following day, Gore murdered her, inflicting trauma to her neck and chest. He then stole her car, a 1986 black Ford Mustang, and dumped her body off a forest road in Columbia County, Florida.[5] On February 14, he attacked a Miami waitress, raping and stabbing her. The waitress survived the attack, and Gore abandoned the stolen Mustang in Miami, where it was found the same day.[6]

On March 11, 1988, 30-year-old Robyn Gayle Novick, a General Motors credit services representative from Lauderhill, who was working a brief stint moonlighting as a dancer, was seen leaving the parking lot of a tavern in her yellow Corvette.[7] She was spotted leaving with a man, who was later identified as Gore. Gore murdered Novick by stabbing her in the chest and tying a belt around her neck. He stole her car and dumped her body in a trash heap near Homestead. According to a medical examiner, the cause of death was mechanical asphyxia and stab wounds. The time of death was estimated between 9 p.m. and 1 a.m. from the late hours of March 11 to the early hours of March 12. In the early hours of March 12, Gore was spotted driving Novick's car. He abandoned the car hours later in Coral Gables, where police found it.[5][6]

Two days later on March 14, Gore attacked a third woman. He abducted 32-year-old Tina Coralis, a nude dancer from Broward.[8] He beat Coralis with a rock, raped her, choked her, stabbed her, then slit her throat with a knife. He left her for dead by the side of a road near to where he had dumped Novick's body.[9] Gore then stole her car and drove off, abducting her 2-year-old son Jimmy, who was still sitting in the back of the vehicle.[5][6]

Capture

Coralis survived the attack and alerted the police. After attacking Coralis, Gore fled the state and headed to Georgia, where he left Jimmy, locking him in the pantry of an abandoned barn before heading north towards Kentucky. On March 16, while police were searching for Jimmy, they came across the body of Novick, who was found near to where Gore had left Coralis. On March 16, Jimmy was found unharmed.[10]

Gore was tracked to a trailer in Paducah, Kentucky. He was captured on March 17, unarmed and without incident. Near to the trailer, police found the stolen car that belonged to Coralis. After he was arrested, Gore was questioned about all three crimes. He initially denied knowing any of the women and tried claiming that he was the biological father of Jimmy. Police showed him photos of Novick's body, which caused his eyes to fill with tears. He then reportedly said, "If I did this, I deserve the death penalty."[10]

In April 1988, Columbia County deputies found Roark's body.[10]

Trial

At Gore's trial, he chose to represent himself. He was convicted of first-degree murder and armed robbery with a deadly weapon. The jury recommended that Gore be sentenced to death by a unanimous vote. Gore made frequent verbal outbursts during his trial and laughed out loud and howled.[10]

In 1998, Gore won a new trial when the Supreme Court of Florida found that the prosecutor had asked him inappropriate questions during his initial trial. In 1999, following a second trial, the jury found him guilty, and he was sentenced to death again.[10] In total, he received two death sentences, seven life sentences, and a further 110 years for his other crimes.[11]

Execution

Gore's execution was rescheduled a total of four times in 2013 alone. He was first scheduled to be executed on June 24, but it was halted because of questions about his sanity.[12] It was rescheduled for July, but halted again due to sanity concerns. Governor Rick Scott then rescheduled the execution for September 10, however, Florida Attorney General Pam Bondi rescheduled the execution date so she could attend a political fundraiser. She later apologized for doing so.[5] Scott then rescheduled the execution for October 1.[13]

On October 1, 2013, Gore was executed via lethal injection at Florida State Prison.[14] His last meal was just a can of Coca-Cola, as he rejected his original requested last meal of sausage and pepperoni pizza. He had no final words.[15][16]

Classification: Murderer

Characteristics: Serial rapist - Robberies

Number of victims: 2

Date of murder: January 31/March 11, 1988

Date of arrest: March 17, 1988

Date of birth: August 17, 1963

Victim profile: Susan Roark, 19 / Robyn Gale Novick, 30

Method of murder: Stabbing with knife - Strangulation

Location: Columbia County, Florida, USA

Status: Sentenced to death on April 3, 1990. Executed by lethal injection on October 1, 2013

Miami killer Marshall Lee Gore is executed at the Florida State Prison

By David Ovalle - MiamiHerald.com

October 1, 2013

STARKE -- Marshall Lee Gore, the notorious Miami rapist and murderer, was known for his outrageous courtroom antics: insulting lawyers, storming off the witness stand and howling at a guilty verdict.

But after more than two decades on Florida’s Death Row, Gore displayed no insolence in his final moments.

Instead, on Tuesday night, as he lay strapped in a gurney awaiting death by lethal injection at Florida State Prison, he refused to open his eyes.

“Inmate Gore, do you have a last statement you’d like to make,” a prison official asked just past 6 p.m.

Gore, 50, his jowls quivering side-to-side slightly, said not a word.

A lethal cocktail of drugs began coursing into his veins through tubes hooked into both arms. Moments later, his mouth opened in a deep labored breath, then stayed agape as color drained from his ruddy face.

From behind a thick pane of glass, four rows of observers, including relatives of victims Robyn Novick and Susan Marie Roark, leaned forward in their chairs as minutes ticked away. A white-smocked doctor walked in. He pried Gore’s eye lids open, shining a light in. No response. At 6:12 p.m., the prison official pronounced Gore dead.

“I thought that was quite ironic, that he had nothing to say at the end,” said retired Miami-Dade Detective Dave Simmons, who investigated Gore’s slew of rapes. “He played the system for years faking insanity, saying outlandish things to judges and witnesses, and in his moment of truth, he had nothing to say for himself. He was the ultimate coward in the end.”

As the relatives filed out of the gallery, Novick’s sister, Pamela Novick, winked at journalists. Gore stabbed and beat Robyn Novick to death in March 1988, leaving her discarded corpse in a trash heap near Homestead.

Pamela Novick recalled her 30-year-old sister’s “heart of gold” and “zest for life” and the horror of her body dumped “as if one was throwing out garbage.”

Novick read a statement after the execution lamenting that Gore had lived for so long after her sister’s death.

“My sister Robyn wasn’t given a choice of how or when she wanted to die,’’ she said. “She was violently murdered by a serial killer with no mercy and no appeals.’’

Novick’s elderly mother, Phyllis Novick, who lives in Ohio, did not attend Tuesday’s execution. Neither did her father.

“Our dearest father, Alvin, had hoped to see this day. Unfortunately, he passed away too soon,” Pamela Novick said.

Gore’s execution was ultimately quick and drama-free, unlike the 25 years of legal wrangling since he murdered the two women and nearly killed another. It had been Gore’s fourth scheduled execution in recent months. Twice before, courts halted executions as Gore’s lawyers sought to stave off his death because of questions about his sanity.

Then, in a move roundly criticized, Florida Attorney General Pam Bondi rescheduled a September execution date so she could attend a political fundraiser; she later apologized. Bondi’s decision still riled many involved in the case.

“It was a slap in the face, not only for the law enforcement officers involved but for the families who have waited 25 long years,” said retired Columbia County Sheriff’s Lt. Neal Nydam, who investigated the Roark murder and attended Tuesday’s execution. Nydam said afterward: “It’s been a roller coaster. But finally, it’s over.”

Nydam attended the execution with former Columbia prosecutor Bob Dekle, who also put away serial killer Ted Bundy. Former Miami-Dade prosecutor Flora Seff also witnessed the execution.

Authorities arrested Gore in 1988 after he kidnapped a stripper Tootsie’s Cabaret in North Miami-Dade. After raping the woman, he slit her throat, bashed her head in with a rock and left her to die in an isolated stretch near Homestead. The woman lived, alerting police officers that Gore had made off with her car, with her 2-year-old son in the back seat. The child was later found alive.

Officers looking for the boy stumbled across Novick’s remains. She was last seen with Gore leaving a tavern.

Novick, originally from Cincinnati, was a General Motors credit services representative who met Gore during a brief stint moonlighting as a dancer at Solid Gold in North Miami-Dade.

Suspicion soon fell on Gore for the disappearance of Tennessee college student Susan Marie Roark, who had disappeared two months earlier. She was last seen in his company. In April 1988, Columbia County deputies found Roark’s body, reduced to almost a skeleton, off a forest road.

In all, Gore was suspected of at least 15 sexual assaults, the attempted murder of a girl in Broward and the two murders.

After he was convicted in a slew of trials, Gore’s lawyers claimed the convicted killer was mentally ill. His execution, they said, would violate a constitutional ban on cruel and unusual punishment. In documents penned himself, Gore tried to prove his insanity by claiming he was being executed as a “human sacrifice” and for “organ harvesting.”

Ultimately, court after court rejected Gore’s claims. Late Tuesday, the U.S. Supreme Court refused to give Gore a final stay.

“I think the system is set up in a way that makes it very difficult for everybody involved, especially the victim’s families,” former prosecutor Seff said. “Despite that fact so much time has passed, the execution brought some peace to these people.”

Gore executed for murder of two Florida women

By Jeff Schweers - Gainesville.com

October 1, 2013

RAIFORD — After 23 years on Death Row, filing appeal after appeal that he was mentally ill and unfit to be put to death, Marshall Lee Gore was executed Tuesday evening as the families of two of his victims watched in silence through a glass window.

Gore, 49, made no last statement and took no sedative before he was killed by lethal injection. The last meal he ordered — a pepperoni and sausage pizza — went uneaten, prison officials said. The state pronounced him dead at 6:12 p.m.

In 1988, Gore was convicted for the brutal slayings of Robyn Gale Novick and Susan Roark. He was also convicted of attempting to murder Tina Coralis and kidnapping Coralis' 2-year-old son. The death warrant was for Novick's murder.

“Robyn Gale Novick was only 30 when Marshall Lee Gore savagely beat, raped, stabbed her in the heart and strangled her to death with her own belt,” Pamela Novick, her sister, said after witnessing Gore's execution.

She choked up and had to start over before continuing the 2½-page handwritten statement.

“He continued to squeeze the life out of her until she took her very last breath,” Novick said, surrounded by other family members. “He then dumped her beautiful body as if one was throwing out garbage.”

Robyn Novick lived in Fort Lauderdale and had been working as an exotic dancer when she met Gore, who killed her and dumped her body in rural Miami-Dade County.

Months earlier, Gore had kidnapped a 19-year-old Roark from Tennessee, using her car, and then killing her and dumping her body in Columbia County.

Members of Roark's family declined to comment, prison officials said.

Pamela Novick said her sister had been a petite, beautiful free spirit who thought people were basically good. “As a free spirit, she enjoyed meeting all types of people,” Pamela Novick said. “Her trusting personality ultimately led to her untimely death.”

Novick also criticized people who empathized with Gore, who got to live for more than two decades, exercising, watching television, breathing and eating, she said. “My sister Robyn wasn't given a choice of how or when she wanted to die.”

Gore was originally scheduled to die on June 24, but an hour before the set time, the federal 11th Circuit Court of Appeals in Atlanta ordered a stay based on a claim by Gore's attorney that Gore was ineligible for execution because he was insane.

A federal appeals court lifted the stay on June 28. Gov. Rick Scott rescheduled the execution for July 10, but Circuit Judge Ysleta McDonald in Bradford County found reasonable grounds that Gore was too insane to be executed following an emergency appeal filed by Gore's attorney.

The Eighth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution prohibits execution of insane inmates. McDonald also ordered more hearings on Gore.

The execution was rescheduled for Sept. 10, but postponed a third time by Gov. Rick Scott at the request of Attorney General Pam Bondi. Bondi had a campaign fundraiser in Tampa on Sept. 10.

The last inmate executed prior to Gore was John E. Ferguson on Aug. 5. He was convicted and sentenced to death for eight counts of first degree murder in 1978. Ferguson's lawyers had made the same argument that he was insane and that executing him would be illegal.

Ferguson understood that he was going to be executed, but he thought he was being targeted in a communist conspiracy, his lawyer said. Ferguson's final statement that he was the prince of God and would rise again also pointed to a lack of understanding about his execution, his lawyers said.

Gore's mental status has long been the subject of numerous motions and appeals by his attorneys, but several judges struck down those claims over the years. His lawyers claimed he was delusional, that his execution was part of a conspiracy among the elite to harvest his organs after he was dead.

Mark Elliott, of Floridians for an Alternative to the Death Penalty, said the state “unnecessarily killed an obviously mentally ill prisoner,” and said the governor should devote more money to solving the thousands of unsolved murders in the state.

Bob Dekle, one of the prosecutors in the case, said he felt empty after watching Gore be put to death. “He did some horrible things to a vast number of undeserving people, and he got what he deserved.” Dekle said. “It took too long.”

On June 14, Scott signed the Timely Justice Act, which requires the governor to sign a death warrant within 30 days of review by the Florida Supreme Court; and it requires the state to execute the defendant within 180 days of the warrant.

The next execution is scheduled for Oct. 15. William Frederick Happ was convicted and sentenced to death in 1989 for the murder of Fort Lauderdale resident Angela Crowley, whose body was found in the Cross-Florida Barge Canal near Crystal River.

On 04/02/88, the skeletonized remains of Susan Roark were found in Columbia County, Florida. Forensic investigation determined that the body was placed in that location at death, or within two hours following death.

Susan Roark was last seen alive on 01/30/88, in Cleveland, Tennessee, in the presence of Marshall Lee Gore. Gore was waiting at a convenience store for a friend to pick him up and travel to Florida. Gore struck up a conversation with Roark and the two left in Roark’s black Ford Mustang.

Gore arrived in Tampa on 01/31/88, driving a black Ford Mustang. He convinced a friend to help him pawn several items that were later determined to have belonged to Roark. Gore then proceeded to Miami, where he abandoned Roark’s car after it was involved in a two-car accident. Gore’s fingerprint and a Miami police traffic ticket, issued to Gore, were found in the car.

Lisa Ingram testified that she was riding in a car with Gore on 02/19/88 when she saw a woman’s purse in the back seat. According to Ingram, Gore told her that the purse belonged to “a girl that he had killed last night.”

Prior Incarceration History in the State of Florida:

Gore had a criminal record in Florida, prior to the Roark murder.

Gore filed a Direct Appeal with the Florida Supreme Court on 05/04/90, citing the following errors: denying a motion to suppress statements to police; allowing the presentation of collateral crime evidence; denying a motion of continuance to secure defense testimony; denying a motion for acquittal on Kidnapping count; failing to sequester Roark’s stepmother; allowing State to question a defense psychiatrist on Gore’s mental state; and finding of aggravating circumstances. On 04/16/92, the FSC affirmed the convictions and sentences of Gore.

Gore filed a Petition for Writ of Certiorari with the U.S. Supreme Court on 09/21/92 that was denied on 11/30/92.

Gore filed a 3.850 Motion with the Circuit Court on 05/03/94 that was denied on 06/04/01.

Gore filed a 3.850 Motion Appeal with the Florida Supreme Court on 07/10/01, citing claims of ineffective assistance of counsel. On 04/17/03, the FSC affirmed the denial of the 3.850 Motion.

Gore filed a Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus with the Florida Supreme Court on 03/27/02, citing claims of ineffective assistance of counsel. On 04/17/03, the FSC denied the Petition.

Gore filed a Pro Se Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus with the U.S. District Court, Middle District, on 10/09/02. On 10/10/02, the USDC denied the Petition, without prejudice, to allow for the completion of State proceedings.

Gore filed a Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus with the U.S. District Court, Middle District, on 09/29/03 and amended the Petition on 04/22/05. The USDC denied the petition on 01/31/06.

Gore filed a Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus with the U.S. Court of Appeals, 11th Circuit, on 03/01/06. The lower court decision was affirmed on 07/20/07, and a mandate was issued on 09/05/07.

Gore filed a pro se 3.853 Appeal with the Florida Supreme Court on 04/12/07, which was denied on 04/08/10.

On 11/16/07, Gore filed a Petition for Writ of Certiorari in the United States Supreme Court. The petition was denied on 02/19/08.

On 07/01/08, Gore filed a 3.850 Motion Appeal in the Florida Supreme Court. This motion was stricken and dismissed by the court on 10/28/08.

On 03/16/88, police found a blue tarp that covered the body of a white female, identified through dental records as Robyn Novick. Forensic investigation showed that the cause of death was multiple stab wounds to the chest and strangulation.

On 03/11/88, witnesses at the Redlands Tavern saw Robyn Novick get into a yellow Corvette and leave the bar, in the company of a man, later identified in photographic lineups as Marshall Gore.

On the morning of 03/12/88, Gore came to the house of David Restrepo, driving a yellow Corvette with “Robyn N” on the license plate. Restrepo was told by Gore that his girlfriend had loaned him the car. Gore and Restrepo then drove to a strip club, and Gore explained that he wanted to change his name to Robyn. The two then went to a convenience store, but after leaving the store, Gore lost control of the vehicle, which flipped several times and came to a rest with two flat tires. Gore and Restrepo abandoned the wrecked car. Police found the abandoned car and discovered credit cards, a driver license, and cigarette case, all belonging to Robyn Novick.

Additional Information:

At the time of conviction for the murder of Robyn Novick, Gore was under a sentence of death for the 01/31/88 kidnapping, robbery, and murder of Susan Roark (Columbia County Case# 88-607) and a sentence of life imprisonment for the 03/14/88 kidnapping, sexual battery, and attempted murder of Tina Corolis (Dade County Case# 88-9827).

In 2002, Gore filed a notice with the Circuit Court that he was incompetent to proceed. The Circuit Court appointed experts for psychiatric evaluation. On 04/09/04, a competency hearing was held in the Circuit Court and Gore was determined to be competent.

Factors Contributing to the Delay in Imposition of Sentence:

Gore’s 1995 convictions and sentences were overturned by the Florida Supreme Court, and he was retried and resentenced in 1999.

Case Information:

On 08/10/95, Gore filed a Direct Appeal with the Florida Supreme Court, citing multiple errors. However, the FSC focused on Gore’s claims that the prosecutor’s questions and comments during cross-examination of Gore and closing arguments were improper. On 10/01/98, the FSC agreed with Gore’s argument and reversed Gore’s convictions and sentences, remanding the case for retrial.

On 02/12/99, Gore was again convicted on all counts of the indictment, and on 04/19/99, was again sentenced to death.

On 07/27/99, Gore filed a Direct Appeal with the Florida Supreme Court, citing the following errors: double jeopardy protections preclude retrial for the murder and robbery charges; denying motion for mistrial for improper witness questioning; denying a motion for judgment of acquittal; admitting improper collateral crime evidence; finding of the aggravating circumstance of cold, calculated, and premeditated murder; allowing Gore to represent himself during the closing argument of the guilt phase and during the penalty phase of trial; and ineffective assistance of counsel during the penalty phase. On 04/19/01, the FSC affirmed the convictions and sentences.

On 06/18/02, Gore filed a 3.850 Shell Motion with the Circuit Court. On 08/27/02, the Circuit Court granted a State motion to strike the 3.850 Shell Motion.

On 10/21/02, Gore filed a 3.850 Motion Appeal with the Florida Supreme Court. On 03/10/03, the FSC ordered Gore to file an amended 3.850 Motion in the Circuit Court within 60 days.

On 06/01/04, Gore filed a 3.850 Motion with the Circuit Court that was denied on 09/13/05.

On 05/31/05, Gore filed a Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus with the Florida Supreme Court that was denied on 09/23/05.

On 10/10/05, Gore filed a 3.850 Motion Appeal with the Florida Supreme Court that was denied on 06/25/09.

On 12/06/08, Gore filed a Petition for Writ of Certiorari in the United States Supreme Court that was denied on 02/23/09.

Supreme Court of Florida

____________

No. SC96127

____________

MARSHALL LEE GORE,

Appellant,

vs.

STATE OF FLORIDA,

Appellee.

[April 19, 2001]

CORRECTED OPINION

PER CURIAM.

We have on appeal the judgment and sentence of the trial court imposing

the death penalty upon Marshall Lee Gore. We have jurisdiction. See art. V, §

3(b)(1), Fla. Const. For the reasons stated below, we affirm the convictions for

first-degree murder and armed robbery and the sentences, including the sentence

of death.

BACKGROUND

This appeal arises from the retrial of Gore as ordered by this Court in Gore

1

At the time of this conviction, Gore was already under sentence of death for the

murder, kidnapping and robbery of Susan Roark, see Gore v. State, 599 So. 2d 978

(Fla.), cert. denied, 506 U.S. 1003 (1992), and a life sentence for the sexual

battery, theft, robbery, burglary and attempted murder of Tina Coralis, see Gore v.

State, 573 So. 2d 87 (Fla. 3d DCA 1991), rev. denied, 583 So. 2d 1035 (Fla.

1991).

-2-

v. State, 719 So. 2d 1197, 1203 (Fla. 1998). Gore was initially tried, convicted of

first-degree murder, and sentenced to death in 1995 for the killing of Robyn

Novick.1

On appeal, this Court reversed the judgment and sentence and ordered a

new trial due to the cumulative effect of the State's improper cross-examination of

Gore and improper closing argument. See id. at 1197. Gore was retried and again

convicted and sentenced to death.

The record of Gore's retrial reflects the following facts. Police discovered

Novick's nude body in a rural area of Dade County on March 16, 1988. Her body

was hidden by a blue tarpaulin-like material. Novick suffered stab wounds to the

chest and had a belt tied around her neck. According to the medical examiner,

Novick died as a result of the stab wounds and mechanical asphyxia.

He

estimated that Novick was killed between 9 p.m. and 1 a.m. on March 11 into

March 12, 1988.

Novick was last seen alive on March 11, 1988, leaving the parking lot of the

Redlands Tavern in her yellow Corvette. A witness testified that Novick left with

-3-

a man, whom the witness identified as Gore.

In the early morning of March 12, Gore was seen driving Novick's

automobile. David Restrepo, a friend of Gore's, testified that Gore arrived at his

home driving a yellow Corvette with a license plate reading "Robyn." Restrepo

had not seen the car before and stated that when he last saw Gore in February

1988, Gore was driving a black Mustang. Gore told Restrepo that his girlfriend

had loaned him the Corvette and asked Restrepo to call him "Robyn." Gore also

asked Restrepo to accompany him to Coconut Grove.

On the way to Coconut Grove, Gore lost control of the vehicle and

"wrecked" the Corvette. Gore attempted to drive the vehicle away from the scene

of the accident, but abandoned the vehicle a few blocks away. Restrepo testified

that shortly after the accident a marked police vehicle was coming towards them,

at which time, Gore told him to "run" because the car was stolen. Gore also told

Restrepo that he had left jewelry in the car.

When the police arrived on the scene,

they recovered credit cards, a driver's license and a cigarette case, all belonging to

Novick, as well as a "power of attorney" executed by Gore.

Jessie Casanova, who was thirteen years old at the time of Novick's murder,

testified that Gore came to her home in the early morning hours of March 12,

driving a yellow Corvette. Gore had been staying with Casanova, her mother, and

2 her mother's friend since February 1988.

According to Casanova, Gore returned to her home later that day, stating that he had been injured in a car accident. At that time, Gore gave Casanova the keys to the Corvette. FBI Special Agent Carl Lowery testified that Novick's body was recovered "within a few hundred feet" from this house.

Williams v. State, 110 So. 2d 654 (Fla. 1959).

-4-

The following night, March 13, Gore went to the house of a friend, Frank

McKee, and asked him if he could borrow some money and stay the night. Gore

stated that the police were looking for him. Gore also informed his friend that he

had recently been in a car accident involving a yellow Corvette and that he had

lost some jewelry. McKee refused to allow Gore to spend the night and Gore

subsequently left in a cab.

In its case-in-chief, the State also introduced Williams2

rule evidence that

Gore committed similar crimes against Roark and Coralis. The State presented

evidence that Gore had murdered Roark shortly after her disappearance in

January 30, 1988, by inflicting trauma to her neck and chest.

In addition, evidence

established that Gore stole Roark's black Ford Mustang and other personal

property, then left her nude body in a rural area used as a trash dump. Similarly,

the State presented evidence that Gore attacked Coralis on March 14, 1988, two

-5-

days after the murder of Novick. Coralis herself testified against Gore, stating that

he beat her with a rock, raped, choked and stabbed her, and left her for dead on the

side of the road near the scene where Novick's body was found. Gore proceeded

to steal Coralis's red Toyota sports car and personal property.

FBI agents finally arrested Gore in Paducah, Kentucky on March 17, 1988.

At the time of his arrest, Gore was in possession of Coralis's red Toyota

automobile and he had her bank and credit cards in the pocket of his jacket.

Police

officers subsequently questioned Gore regarding the Coralis and Roark crimes.

According to the police, Gore denied knowing Roark or Coralis and denied all

involvement in the crimes. Gore also denied knowing Novick. When police

prepared to show Gore a photograph of Novick, Gore stated "just make sure it is

not gory" because his "stomach could not take it." At the time that Gore made

such statements, the police had yet to inform Gore that Novick was dead.

Detective David Simmons of the Miami-Dade Police Department testified that

when Gore looked at Novick's picture, Gore's eyes "swelled with tears." Gore also

stated that "if I did this, I deserve the death penalty."

In his defense, Gore took the stand and testified on his own behalf. Gore

claimed that prior to his interrogation by police in Miami concerning the Novick

murder, reporters previously had told him upon his arrest that Novick was dead.

3

Gore's claims concerning the officers' use of gruesome photographs and that he

was given a lie detector test were refuted by Detective Steven Parr and Detective

Lou Passaro of the Miami-Dade Police Department. Both testified during the

State's rebuttal.

-6-

He also claimed that during his interrogation, police had placed gruesome

photographs of the murders all over the interview room. Moreover, Gore stated

that police had given him a polygraph examination, which he claimed he had

passed.3

Gore testified that he was the owner of an escort service and claimed that

Coralis, Novick, Roark, and Restrepo all worked for the escort business.

Gore

maintained that Novick worked for him as a nude dancer and he admitted that he

was with Novick at the Redlands Tavern on the evening of March 11, 1988. Gore,

however, denied killing her. Gore explained that he was driving Novick's

Corvette and that he had arranged for both Novick and Coralis to work as escorts

that night. Gore claimed that after leaving the Redlands Tavern, he drove Novick

to a club where Coralis worked. According to Gore, Novick, Coralis, and another

woman left the club with three men in a Mercedes. Gore claimed that he followed

this group in Novick's vehicle to a warehouse in Homestead, Florida. Gore stated

that he called the warehouse later that night and that the phone was answered by a

member of a pro-Castro group, with which one of the men was affiliated.

Gore testified that he spoke with Novick later that night and informed her

-7-

about the accident and told her to report the car stolen so that she could collect the

insurance proceeds. During this conversation, Novick told Gore that Coralis had

left in the middle of the night because there were "problems" with the three clients

who were angry about missing drugs and drug money. Gore claimed that he knew

that Coralis previously had sold some drugs and used the proceeds to buy a new

car.

Gore also testified that he spoke with Coralis a few days later, and that she

was scared because someone was looking for her. Gore claimed that Coralis

wanted a gun and that he had arranged a meeting with her in an effort to assist

Coralis in selling the remainder of her drugs. Furthermore, Gore claimed that he

later saw the men who were with Novick and Coralis on the night of the Novick

murder and they told him that Novick "was picked up" from the warehouse.

Addressing his relationship with Susan Roark, Gore admitted that he knew

her for many years. He acknowledged that he was with Roark on the last night

that she was seen alive. He stated, however, that Roark had visited him during his

incarceration in Miami, indicating that it was impossible for him to have murdered

Roark. Gore also asserted that Dr. William Maples, a forensic anthropologist,

could testify that Roark had been dead for only three weeks when her remains

were recovered and that Gore had been in jail for six months at that time.

Furthermore, Gore asserted that the evidence found at the site where Roark's body

was found did not link him to the crime.

On cross-examination, Gore admitted that he previously had been convicted

of committing fifteen felonies. Gore denied trying to kill Coralis and claimed that

her injuries were the result of her jumping out of a moving car. Gore also asserted

that all of the State witnesses had lied and he refused to explain why he was in

possession of the property of people who were either killed or attacked.

Ana Fernandez testified on Gore's behalf. Fernandez worked for Gore in

1984 or 1985 when she was fifteen years old, answering phones for the escort

service. Fernandez claimed to have known Roark, Coralis, and Novick through

her association with Gore. However, she could not state when, where, or how

many times that she had met Coralis or Novick and was unable to describe them.

Moreover, when presented with a photograph of several women, she could not

identify Coralis.

After the close of all the evidence, the jury convicted Gore of first-degree

murder and armed robbery with a deadly weapon of Novick. During the penalty

phase, Gore chose to represent himself. The jury recommended that Gore be

sentenced to death by a vote of twelve to zero. The trial court imposed the death

penalty for the first-degree murder conviction and imposed an upward departure

4

This aggravating circumstance pertained to the first-degree murder, kidnaping

and robbery of Susan Roark, and the attempted first-degree murder, sexual battery,

armed burglary, armed robbery, and armed kidnaping of Tina Coralis.

5

Raul and Marisol Coto are the parents of Jessie Casanova. According to

Casanova's penalty phase testimony, while Gore was living with Casanova,

Marisol Coto, and Rosa Lastra, Gore broke-up an altercation between Raul and

Marisol and stopped Raul from becoming violent.

-9-

life sentence for the armed robbery conviction to run consecutive to any other

sentence Gore was serving.

In its sentencing order, the trial court found the following three aggravating

circumstances: (1) Gore was previously convicted of another capital felony

involving the use or threat of violence to the person;4

(2) the capital felony was

committed while Gore was engaged in the commission of, or an attempt to

commit, or in flight after committing or attempting to commit any robbery; and (3)

the capital felony was committed in a cold, calculated and premeditated manner

without any pretense of legal justification ("CCP"). The trial court found no

statutory mitigating circumstances, but did find three nonstatutory mitigating

circumstances: (1) Gore suffered hearing loss (minimal weight); (2) Gore suffered

from migraine headaches (minimal weight); and (3) Gore had previously stopped

an altercation between Raul and Marisol Coto (minimal weight).5

The trial court

concluded that the aggravators outweighed the mitigators and sentenced Gore to

6

Gore raises the following issues: (1) the Double Jeopardy Clause of the United

States and Florida Constitutions prevented the State from retrying Gore for firstdegree murder and armed robbery; (2) the trial court erred in denying his motion

for a mistrial following the State's questioning of Jessie Casanova about whether

she had an "intimate relationship" with Gore; (3) the trial court erred in denying

Gore's motion for a judgment of acquittal on charges of first-degree murder and

armed robbery; (4) the trial court abused its discretion in excluding reverse

Williams rule evidence pertaining to the murder of Paulette Johnson, which

allegedly supported Gore's hypothesis of innocence; (5) the State introduced

improper collateral crime evidence during the penalty phase; (6) the trial court

erred in finding and weighing the CCP aggravating circumstance; (7) the trial

court erred in permitting Gore to represent himself during the guilt phase closing

argument and during the penalty phase of trial; and (8) Gore received ineffective

assistance of counsel during the penalty phase.

-10-

death.

Gore raises eight issues in this appeal. 6

We address the guilt-phase issues

first.

GUILT PHASE

A. Double Jeopardy

In the first issue, Gore claims that by retrying him in this case, the State

violated his constitutional rights by placing him in double jeopardy. Relying on

Oregon v. Kennedy, 456 U.S. 667 (1982), Gore asserts that the State's actions

during cross-examination of Gore and closing argument were so egregious that

this Court should find that the Double Jeopardy Clause of both the United States

and Florida Constitutions prevented the State from retrying him in this case.

-11-

As stated by the United States Supreme Court in Kennedy, the Double

Jeopardy Clause would prevent the State from retrying a defendant where it is

established that the judge or prosecutor, by his or her own egregious conduct,

caused the defendant to move for a mistrial, and the conduct of the judge or

prosecutor "was intended to provoke the defendant into moving for a mistrial."

456 U.S. at 679. "Only where the governmental conduct in question is intended to

'goad' the defendant into moving for a mistrial may a defendant raise the bar of

double jeopardy to a second trial after having succeeded in aborting the first on his

own motion." Id. at 676. Despite this limited exception barring a retrial, the

Double Jeopardy Clause's general prohibition against successive prosecutions

does not prevent the State from retrying a defendant who succeeds in getting his

conviction set aside on appeal due to some error in the proceedings below. See

Lockhart v. Nelson, 488 U.S. 33, 38 (1988); see also Ruiz v. State, 743 So. 2d 1,

9-10 n.11 (Fla. 1999) (holding that double jeopardy did not bar State from retrying

defendant despite the fact that prosecutors "attempted to tilt the playing field and

obtain a conviction and death sentence"); Keen v. State, 504 So. 2d 396, 402 n.5

(Fla. 1987) (holding double jeopardy did not prevent a retrial of defendant arising

from prosecutorial misconduct).

Gore's reliance on Kennedy is misplaced. In the present case, Gore did not

-12-

successfully abort the first trial pursuant to a motion for a mistrial. Rather, Gore's

convictions were overturned on appeal. Thus, the limited Kennedy exception to

the Double Jeopardy Clause does not apply here and it was not error for the State

to retry Gore despite the prosecutors' actions in the first trial. See Ruiz, 743 So. 2d

at 10 n.11; Keen, 504 So. 2d at 402 n.5.

B. Motion for a Mistrial

In the second issue, Gore claims that the trial court erred in denying his

motion for a mistrial after the State questioned Jessie Casanova, in the course of

her testimony as a State witness, about whether she had an "intimate relationship"

with Gore. Gore contends that the State's question was unfairly prejudicial

because Casanova was only thirteen years old at the time of the murder.

Immediately following the State's question, defense counsel objected on

grounds that such questioning was improper Williams rule evidence and

subsequently moved for a mistrial. The trial court denied the motion for a

mistrial. However, the trial court sustained the objection and gave the following

instruction to the jury:

The last objection was sustained. I'm going to strike

from the record the last response made by the witness.

You must disregard it in your deliberations. Are you all

able to follow the instruction? Is there anyone at all who

would be influenced in any way by the last responses

you just heard from the witness? If so, just raise your hand. For the record, I see no hands. All jurors said they

could follow that instruction.

A ruling on a motion for a mistrial is within the sound discretion of the trial

court and should be "granted only when it is necessary to ensure that the defendant

receives a fair trial." Goodwin v. State, 751 So. 2d 537, 547 (Fla. 1999) (quoting

Cole v. State, 701 So. 2d 845, 853 (Fla. 1997)). Moreover, as this Court stated in

Goodwin, the use of a harmless error analysis under State v. DiGuilio, 491 So. 2d

1129 (Fla. 1986), is not necessary where "the trial court recognized the error,

sustained the objection and gave a curative instruction." 751 So. 2d at 547.

We hold that the trial court did not abuse its discretion in denying Gore's

motion for a mistrial. This single question is in marked contrast to the error in the

first trial when on three separate occasions during cross-examination of Gore, the

prosecutor questioned Gore as to whether he had sex with a thirteen-year-old girl

(referring to Casanova). See Gore, 719 So. 2d at 1200. In the first trial, the trial

court overruled defense counsel's timely objections to these questions. See id. In

addition, our reversal resulted from the cumulation of multiple errors throughout

the trial caused by the conduct of the prosecutor. See id. at 1202-03.

In the present case, the State asked Casanova one isolated question

regarding the nature of her relationship with Gore. The trial court sustained the

objection and immediately instructed the jury to disregard Gore's relationship with

-14-

Casanova, and the State did not refer to Gore's relationship with Casanova during

closing argument. Any prejudice that may have ensued from the State's improper

question was exacerbated by Gore himself, who referred to the improper

relationship with thirteen-year-old Casanova on several occasions during the

State's cross-examination of Gore despite the fact that the State did not initiate any

additional questions about Gore's relationship with Casanova. Accordingly, we

hold that the trial court did not abuse its discretion in denying Gore's motion for a

mistrial. See Walker v. State, 707 So. 2d 300, 313 (Fla. 1997); Cole, 701 So. 2d at

853.

C. Motion for Judgment of Acquittal

Gore contends that the trial court erred in failing to grant his motion for a

judgment of acquittal on charges of first-degree murder and armed robbery. Gore

argues that the circumstantial evidence does not prove that Gore killed Novick

with a premeditated design, or during the commission of a felony, as is necessary

to support a finding of guilt for first-degree murder. In addition, Gore argues that

the State presented insufficient evidence to support his conviction for armed

robbery.

As stated in Orme v. State, 677 So. 2d 258, 262 (Fla. 1996), a motion for

judgment of acquittal should be granted in a circumstantial evidence case if the

7

The State sought a first-degree murder conviction on alternative theories of

premeditated murder and felony-murder with the underlying offenses of armed

robbery. See Griffin v. United States, 502 U.S. 46, 47 (1991) (stating that even if

the evidence does not support the specific verdict, any error in charging the jury

on that theory is harmless where the evidence supports a conviction for the general

verdict). Because a general verdict form was used in this case, in order to affirm

Gore's first-degree murder conviction, competent substantial evidence must exist

to support either premeditated or felony-murder (predicated on armed robbery).

-15-

State fails to present evidence from which the jury can exclude every reasonable

hypothesis except that of guilt. See id. (citing State v. Law, 559 So. 2d 187, 188-

89 (Fla. 1989)).

[The court's] view of the evidence must be taken in the light most

favorable to the state. The state is not required to "rebut conclusively

every possible variation" of events which could be inferred from the

evidence, but only to introduce competent evidence which is

inconsistent with the defendant's theory of events.

Law, 559 So.2d at 188-89 (citations and footnote omitted) (quoting State v. Allen,

335 So. 2d 823, 826 (Fla. 1976)). "In sum, the sole function of the trial court on

motion for directed verdict in a circumstantial-evidence case is to determine

whether there is prima facie inconsistency between (a) the evidence, viewed in the

light most favorable to the State and (b) the defense theory or theories." Orme,

677 So. 2d at 262. If such inconsistency exists, then the question is for the finder

of fact to resolve. See Woods v. State, 733 So. 2d 980, 985 (Fla. 1999). The trial

court's finding will not be reversed on appeal if there is competent substantial

evidence to support the jury's verdict.7

See id.; Orme, 677 So. 2d at 262.

See Jones v. State, 748 So. 2d 1012, 1024 (Fla. 1999) (citing Mungin v. State, 689

So. 2d 1026, 1029-30 (Fla. 1995)). In addition, competent substantial evidence

must exist to support Gore’s conviction for armed robbery.

-16-

1. Premeditated Murder

We first examine Gore's contention that the trial court erred in failing to

grant a judgment of acquittal on the first-degree murder charge because the State

failed to present sufficient evidence to support premeditated murder.

"Premeditation is defined as more than a mere intent to kill; it is a fully formed

conscious purpose to kill." Green v. State, 715 So. 2d 940, 943 (Fla. 1998). This

purpose to kill must exist for sufficient time before the homicide "to permit

reflection as to the nature of the act to be committed and the probable result of that

act." Id. at 944. Premeditation can be shown by circumstantial evidence. See

Woods, 733 So. 2d at 985. As this Court has stated:

Evidence from which premeditation may be inferred includes such

matters as the nature of the weapon used, the presence or absence of

adequate provocation, previous difficulties between the parties, the

manner in which the homicide was committed, and the nature and

manner of the wounds inflicted.

Green, 715 So. 2d at 944 (quoting Holton v. State, 573 So. 2d 284, 289 (Fla.

1990)).

Applying these principles to this case, we hold there is competent

substantial evidence supporting Gore's conviction for premeditated murder of

-17-

Novick and to rebut Gore's hypothesis of innocence. The official cause of

Novick's death was stab wounds to the chest associated with mechanical

asphyxiaBstrangulation. One of the stab wounds to Novick's chest was so deep

that it penetrated her heart and lung. This wound was severe enough to cause

Novick's death. However, while Novick was still alive, she was strangled with a

silver belt so forcefully that she suffered a fracture of her trachea. There were no

defensive wounds found on Novick's body and no evidence was presented

indicating that the murder was the result of a provocation or ill will between

Novick and Gore.

The State presented additional evidence to support a conviction of

premeditated murder, including Gore's history of targeting young, attractive

women who drove sporty automobiles and thereafter killing or attempting to kill

them. The State points to the fact that in this case, as in the prior similar crimes,

Gore did not attack these women in haste as evidenced by the fact that no blood or

any other physical evidence of foul play was found in the victims' vehicles.

Rather, the evidence suggests that Gore acted with deliberation by removing the

victims from their vehicles prior to stabbing them. Further, there was no evidence

that any of the victims resisted or struggled with Gore, an indication that Gore

acted calmly and with deliberation.

-18-

Based upon the circumstantial evidence presented in this case, we hold that

there was competent substantial evidence supporting the jury's first-degree murder

verdict. See Crump v. State, 622 So. 2d 963, 971 (Fla. 1993) (holding sufficient

evidence of premeditation existed to support jury's verdict where defendant struck

and then strangled victim and had engaged in a pattern of similar crimes).

Accordingly, the trial court did not err in denying Gore's motion for a judgment of

acquittal.

2. Felony Murder and Armed Robbery

The State contends that even if the evidence did not support premeditated

murder, the evidence does support Gore's conviction based upon a felony murder

theory. We agree. Robbery is "the taking of money or other property which may

be the subject of larceny from the person or custody of another when in the course

of the taking there is the use of force, violence, assault, or putting in fear."

§ 812.13(1), Fla. Stat. (1989). Property that is the subject of the taking need not

be in the actual physical possession or immediate presence of the person who was

robbed. See Jones v. State, 652 So. 2d 346, 350 (Fla. 1995). "Property is taken

from 'the person or custody of another' if it is sufficiently under the victim's

control so that the victim could have prevented the taking if she had not been

subjected to the violence or intimidation by the robber." Id. Under section

-19-

812.13(3)(b), Florida Statutes (1989), the violence or intimidation may occur prior

to, contemporaneously with, or subsequent to the taking of the property so long as

both the act of violence or intimidation and the taking constitute a continuous

series of acts or events. See Jones, 652 So. 2d at 349. The taking of property after

a murder, however, does not constitute robbery if the motive for the murder was

not the taking of property. See Mahn v. State, 714 So. 2d 391, 397 (Fla. 1998)

(citing Knowles v. State, 632 So. 2d 62, 66 (Fla. 1993), Clark v. State, 609 So. 2d

513, 515 (Fla. 1992), and Parker v. State, 458 So. 2d 750, 754 (Fla. 1984)).

We hold that there is competent substantial evidence to support the finding

that Gore committed murder during the commission of a robbery. In the present

case, Novick was last seen alive driving her Corvette from the Redlands Tavern,

accompanied by Gore, who admitted to being with Novick at the bar that evening.

Hours later, Gore was seen driving the Corvette, without Novick, telling others

that the car was on loan from his girlfriend. After wrecking the car, he abandoned

it and stated that it was stolen. Inside the vehicle, police recovered Novick's

personal property and a "power of attorney" executed by Gore. The day after

Gore wrecked the car, Gore gave a friend the keys to the vehicle and told another

friend that the police were after him. Novick's body was found several days later,

naked and abandoned in a remote area, within a few blocks from where Gore had

-20-

attacked Tina Coralis and from where Gore previously had been staying.

The evidence also revealed that when Gore took Novick's Corvette, he did

not have a car of his own. Gore's prior convictions established a pattern of

attacking women in order to gain their property and use their cars. In each of

these prior instances, Gore attempted to murder or actually murdered women, stole

their personal possessions and cars, and left the bodies in remote areas.

In sum, there is competent substantial evidence supporting Gore's

conviction for armed robbery. Therefore, we hold that the trial court did not err in

denying Gore's motion for a judgment of acquittal on charges of first-degree

murder and armed robbery.

D. Reverse Williams Rule Evidence

In this claim, Gore contends that the trial court erred in excluding reverse

Williams rule evidence pertaining to the murder of a Paulette Johnson, which Gore

argues supports his hypothesis of innocence. Gore alleges that Johnson was a

woman from Miami who worked for his escort service and who was murdered in

Tennessee in 1989 in the very same manner as both Novick and Coralis were

murdered. Gore argues that because he was incarcerated at the time of Johnson's

death, evidence of Johnson's murder supported his assertions that someone else

had murdered Novick.

8

Despite the trial court's ruling to exclude any reference to the murder of Paulette

Johnson, Gore violated the trial court's order by discussing the murder during his

-21-

Prior to trial, the State filed a motion in limine to prevent Gore from

introducing evidence relating to the alleged murder of Paulette Johnson. The State

argued that the murder of Johnson was insufficiently similar to the murders of

both Novick and Roark to be admissible. In addition, the State contended that the

woman murdered in Tennessee was actually named "Pauline Johnson," not

"Paulette Johnson." Thus, the State argued that Gore failed to present sufficient

evidence demonstrating that "Pauline Johnson" was the same "Paulette Johnson"

who Gore claimed worked for his escort service. Furthermore, the State argued

that any testimony concerning the death of Johnson was hearsay and inadmissible

because Gore could not satisfy the test for admissibility of similar fact evidence of

other crimes for exculpatory purposes. The trial court granted the State's motion

stating that Gore could not establish that Pauline Johnson, the woman murdered in

Tennessee, was the same Paulette Johnson who Gore claimed was involved in his

escort business. In addition, the court ruled that Gore failed to show how the

murder was relevant in this case.

Although the issue was revisited at trial, the court again excluded all

testimony pertaining to the death of Johnson because Gore could not satisfy the

test for admissibility by demonstrating the necessary relevance of the evidence.8

Gore now argues on appeal that the trial court erred in excluding this evidence

because it could have established reasonable doubt as to his guilt in the murder of

Novick.

In Rivera v. State, 561 So. 2d 536, 539-40 (Fla. 1990), this Court addressed

the situation where a defendant, standing trial for murder, attempted to raise

reasonable doubt in jurors' minds by introducing evidence that a murder of a

similar nature had been committed by someone other than the defendant and that

the murder occurred while the defendant was in police custody. In addressing the

matter, this Court stated that

where evidence tends in any way, even indirectly, to establish

reasonable doubt of defendant's guilt, it is error to deny its admission.

§ 90.404(2)(a), Fla. Stat. (1985). However, the admissibility of this

evidence must be gauged by the same principle of relevancy as any

other evidence offered by the defendant.

Id. at 539; see State v. Savino, 567 So. 2d 892, 894 (Fla. 1990) (defendant must

demonstrate "a close similarity of facts, a unique or 'fingerprint' type of

information" in order to introduce evidence of another crime to show that someone

other than the defendant committed the instant crime).

In this case, Gore sought to introduce evidence pertaining to the murder of

Pauline Johnson, which allegedly occurred while Gore was in police custody,

9

These findings included the following: (1) Gore had a history of targeting

young, attractive women who drove new sporty automobiles; (2) Gore previously

was convicted of murdering Susan Roark after stabbing her to death, stealing her

car and jewelry, and dumping her body in a remote area; (3) Gore did not have his

own automobile and theft of Novick's automobile "was one of the motivating

factors" for the murder, but "was clearly not the Defendant's sole plan"; (4) Gore

murdered Novick after a "well thought-out attack," as indicated by the fact that

Novick was stabbed and strangled to death, she had no defensive wounds, and her

nude body was left in a remote area, "one which [Gore] reasonably believed would

hide the body until nature, insects and other predators would erase any identifying

evidence of the victim"; (5) Gore used the same modus operandi in the murders of

Novick, Roark, and the attempted murder of Coralis; (6), Gore took his victims'

jewelry and automobiles after committing murder or attempted murder; (7) Gore

did not panic or act hastily and attack any of these women in their cars, as

evidenced by the fact that no blood or any other physical evidence of foul play

was found in the cars; rather, Gore acted calmly and with deliberation when he

-23-

claiming that this murder was committed in a similar manner to the murders of

Novick and Roark. However, Gore did not proffer the underlying facts of the

Johnson murder to the trial court to enable the court to determine whether the

murder was relevant and sufficiently similar to Novick's murder to warrant

admissibility. Therefore, because Gore failed to show the relevance and requisite

similarities between this case and the killing of Johnson, the trial court did not

abuse its discretion in excluding evidence pertaining to the murder of Johnson.

PENALTY PHASE

A. CCP Aggravating Circumstance

In the present case, the trial court made extensive findings in support of the

CCP aggravating circumstance.9

Nevertheless, Gore claims that the trial court

removed each victim from her vehicle prior to stabbing her; (8) there was no

evidence to suggest that any of his victims resisted or struggled with Gore, also

indicating that Gore acted calmly and deliberately when he took Novick's life; (9)

Novick's injuries demonstrate that the killing was not prompted by an emotional

frenzy, panic, or fit of rage--Novick suffered two stab wounds to the neck and an

injury to her neck and trachea caused by the extensive pressure applied by Gore

during the strangulation; and (10) Novick was alive while being stabbed and

strangled and eventually bled to death.

-24-

erred in finding and weighing this aggravator. We disagree. In order to prove the

existence of the CCP aggravator, "the State must show a heightened level of

premeditation establishing that the defendant had a careful plan or prearranged

design to kill." Bell v. State, 699 So. 2d 674, 677 (Fla. 1997). A trial court's

ruling on an aggravating circumstance will be sustained on review as long as the

court applied the right rule of law and its ruling is supported by competent

substantial evidence in the record. See Almeida v. State, 748 So. 2d 922, 932 (Fla.

1999) (citing Willacy v. State, 696 So. 2d 693, 695 (Fla. 1997)).

The facts of this case clearly support a finding of a heightened level of

premeditation and this Court previously has affirmed findings of CCP under

similar circumstances. See Wuornos v. State, 644 So. 2d 1000, 1008-09 (Fla.

1994) (affirming trial court's finding of CCP where evidence established that

defendant lured victim to an isolated area, killed victim, and proceeded to steal

victim's property, and defendant had previously killed multiple victims in similar

manner). Based on our review of the record, we find that the trial court did not err

10 Gore also argues that several of the trial court's factual findings enunciated in

its sentencing order pertaining to CCP were not supported by the evidence. In

particular, Gore challenges the court's finding that after stabbing Novick, Gore

"looked her in the eye (since she was lying on her back, facing upward) and

strangled the last bit of life out of her." In this case, there was no direct testimony

that Gore looked Novick in the eye as he was killing her, and the medical

examiner testified that he could not be certain whether Novick's eyes were open or

closed at the time of her death. Although Gore may have "looked [Novick] in the

eye" as he was killing her, there is no evidence in the record to support the trial

court's finding or to rule out other scenarios. Thus, we conclude that the trial

court's description of the final moments of the homicide was based upon

speculation. See Knight v. State, 746 So. 2d 423, 435 (Fla. 1998). However, we

find this inclusion harmless in view of the other strong evidence supporting the

trial court's multiple findings that support the CCP aggravating circumstance. See

id. at 436.

-25-

in finding this aggravating circumstance.10

B. State's Impeachment of Gore

Gore also argues that the State improperly questioned him on cross

examination during the penalty phase about collateral crimes allegedly committed

by Gore against other women. Gore argues that the State's questioning

constituted improper Williams rule evidence and was admitted solely to

demonstrate Gore's bad character or propensity to commit crime. We disagree and

hold that Gore opened the door to this line of questioning by placing his

propensity for violence in issue by stating that he was "not a violent person."

There is a different standard for judging the admissibility and relevance of

evidence in the penalty phase of a capital case than during the guilt phase,

11 We distinguish what took place here from what occurred in Gore's first trial. In

Gore's first appeal, this Court held that the State's questioning of Gore about

collateral acts of violence directed at Maria Dominguez was improper because it

"could only demonstrate Gore's bad character or propensity to commit crime."

Gore, 719 So. 2d at 1200. Importantly, in that case, the State's questions came

-26-

especially where the focus of the evidence is directed towards the character of the

defendant. See Hildwin v. State, 531 So. 2d 124, 127 (Fla. 1988). As this Court

has stated:

[D]uring the penalty phase of a capital case, the state may rebut

defense evidence of the defendant's nonviolent nature by means of

direct evidence of specific acts of violence committed by the

defendant provided, however, that in the absence of a conviction for

any such acts, the jury shall not be told of any arrests or criminal

charges arising therefrom.

Id. at 128; see Smith v. State, 515 So. 2d 182, 185 (Fla. 1987) (stating that the

State properly presented evidence of defendant's prior manslaughter conviction

during the penalty phase after defense witness testified that the defendant "would

never harm anyone").

Similar to Hildwin, in the present case, Gore placed his character in issue by

taking the stand and testifying "you heard that I'm not or not known as a violent

person, and I'm not a violent person." In doing so, Gore opened the door to the

State's impeachment evidence and the State proceeded to properly question Gore

about his collateral acts of violence towards women to impeach Gore's assertions

that he was a nonviolent person.11 We hold that the State's questioning was proper

during the guilt phase of trial and Gore had not placed his character in issue by

claiming that he was a nonviolent person.

-27-

rebuttal and the trial court did not err in allowing the State to question Gore about

his prior acts of violence.

C. Gore's Self-Representation During Penalty Phase

Gore next contends that his decision to represent himself in the guilt phase

closing argument and during the penalty phase was not knowing and voluntary, as

required by Faretta v. California, 422 U.S. 806, 835 (1975), because he was forced

to choose between proceeding pro se or being represented by incompetent counsel.

Despite Gore's unequivocal requests at trial that he be permitted to represent

himself, he now argues that the trial court erred in permitting him to proceed pro

se during the guilt phase closing argument and penalty phase proceedings.

We detail the actual proceedings related to this claim in order to properly

evaluate Gore's assertions. Prior to the retrial in this case, Gore first complained

to the trial court about the way his attorney was proceeding on several issues,

including the admission of Williams rule evidence, and Gore requested that he be

allowed to represent himself. Before allowing Gore to proceed pro se, in

accordance with Faretta, the court inquired as to why Gore wanted to remove

counsel and represent himself and determined whether Gore was competent to do

so. The trial court instructed Gore of the advantages of having appointed counsel

-28-

and the disadvantages of self-representation. The court also instructed Gore that

should he choose to proceed pro se, he would be required to abide by the rules of

criminal law and courtroom procedure. In addition, the trial court asked Gore

several questions to determine whether he was competent to make a knowing and

intelligent waiver of counsel. Among other areas, the court inquired into Gore's

educational background, whether he was currently under the influence of drugs

and alcohol, and whether he had physical or mental problems that would hinder

his self-representation. The court concluded that Gore understood the dangers and

disadvantages of self-representation and that he was competent to make a knowing

and intelligent waiver of counsel.

At a subsequent hearing, however, Gore changed his mind and requested

that his attorney be reappointed. The trial court granted Gore's request. However,

immediately following the State's opening statements, Gore again informed the

court that he was unhappy with the manner in which defense counsel was

representing him and stated that he wished to represent himself for the remainder

of the trial. After discussing the matter with the court, Gore changed his mind and

stated that he did not wish to represent himself.

Despite proceeding through trial represented by defense counsel, Gore

informed the trial court, prior to the guilt phase closing arguments, that he wanted

12

Nelson v. State, 274 So. 2d 256 (Fla. 4th DCA 1973).

13 The following discussion took place at sidebar regarding Gore's request of

counsel that he be recalled to testify:

DEFENSE COUNSEL: My client wants to take the stand

again and I don't believe from what I – because I asked him to tell me

what relevant testimony do you have that was not discussed in your

prior testimony? He wrote out some questions and whatnot, but gave

me nothing relevant. Stupid questions. Why you should find me not

guilty and things like that.

THE COURT: Well, if you have no relevant questions to ask

him, what would be the point of him taking the stand? He can't take

the stand just to make a statement to the jury.

. . . .

If you don't have any questions to ask him, I don't see what we

are addressing really.

DEFENSE COUNSEL: I'm just concerned from a

constitutional standpoint, if my client's right to testify extends to

testifying more than once.

THE COURT: Well, what I'm saying is, I don't think I need to

get to that juncture, if you have no further questions of your client.

There is no reason for him to take the stand and we don't need to

-29-

to be "lead counsel" and to conduct closing argument himself. Gore stated that

defense counsel deprived him of his right to testify, referring to the fact that

defense counsel would not recall Gore to testify following the State's rebuttal case.

In accordance with Nelson,

12 the trial court inquired into Gore's allegations.

Defense counsel explained to the trial court that he had discussed the issue

extensively with Gore and explained to him that the additional testimony that Gore

had proposed was irrelevant.13 Before allowing Gore to conduct the guilt phase

closing argument pro se, the trial court reminded Gore of the rights and pitfalls

pertaining to self-representation. Furthermore, the trial court reviewed the

transcript of the prior pretrial Faretta hearing and informed Gore about the

responsibilities of self-representation. Gore claimed that he understood the court's

instructions and proceeded to conduct his own closing argument.

At the conclusion of the closing arguments, Gore requested that counsel be

reappointed for the penalty phase proceedings. Although the trial court initially

granted Gore's request, Gore subsequently changed his mind and asked that he be

permitted to represent himself during the penalty phase. Gore claimed that he was

forced to proceed pro se during the penalty phase because defense counsel failed

to secure any mental health experts or fact witnesses to testify on Gore's behalf for

purposes of introducing mitigating evidence.

Appointed counsel was given the opportunity to explain to the court why he